It was dark out still. Very dark, in fact. It was 3 in the morning and my brothers and I were on our way to Tarlac, a 2-hour-with-no-traffic drive from Manila. I measure road trips back home using hours and not kilometers since one never knows what kind of mess one will find on the road. I was actually very impressed with how highways have greatly improved since the last time I visited but driving anywhere in the Philippines is still very unpredictable. We were determined to reach Santa Juliana before sunrise. And so we did.

Santa Juliana is a small town in the province of Tarlac, northwest of Manila. This was where we would meet two locals from the Pinatubo Spa Town, one would drive us in a 4×4 jeep across Crow Valley and the other would hike with us to the crater lake of Mount Pinatubo. We actually arrived a little too early. An old man sitting on a makeshift cart towed by a hefty carabao greeted us and told us that the treks wouldn’t start until 7 in the morning. We had an hour to kill but it was perfectly fine. I didn’t mind waiting as long as I’d get to see Pinatubo. I would be flying back to San Francisco in a couple of days and I didn’t want to take any chances and get there too late. We already did the week before when we arrived horribly late and unprepared. We didn’t know that the Pinatubo treks have become so popular that a reservation is a must when planning a weekend trip to see the crater lake.

It’s been almost twenty years since Pinatubo erupted, spewing huge clouds of volcanic ash and acid gases way up in the air. Pinatubo was relatively unknown, a volcano with no records of major eruptions, until that fateful June of 1991. Some reports pegged the Pinatubo eruption as the largest disturbance in the stratosphere since the eruption of Krakatau in 1883, significantly affecting not only the Philippines but the entire planet.

I remember those days very well when virtually everything was blanketed in ash. Cars in the street. Rooftops. Church pews. School desks. Even my glasses were thinly coated with volcanic ash as I walked down our neighborhood. And that was in Manila, which is over 60 miles away from the volcano. There were hundreds of fatalities and hundreds of thousands of families that were left homeless in the three provinces surrounding Pinatubo — Tarlac, Zambales and Pampanga. Even the United States’ two military bases, Clark and Subic, were not spared. But those who were hardest hit were the Aetas, the indigenous natives who lived in the dense jungles near and around the volcano. The blast drove them out of where they lived and where they made a living. And the damage caused by the eruption didn’t end quickly. Because Pinatubo expelled voluminous amounts of pyroclastic material, widespread and massive lahars or pyroclastic mudflows threatened the lives and properties of so many Filipinos even years following the blast.

After the eruptions ended and volcanic dust finally settled, a crater lake formed in Pinatubo’s caldera, the large depression formed by the collapse of the center of the volcano. Initially, the lake was hot and highly acidic but as the years passed by, rainfall cooled and diluted the lake.

“The lake increased in depth by about 1 meter [approximately 3 feet] per month on average, until September 2001, when fears that the walls of the crater might be unstable prompted the Philippine government to order a controlled draining of the lake. 9,000 people were once again evacuated from surrounding areas in case a large flood was accidentally triggered. Workers cut a 5-meter notch in the crater rim, and successfully drained about a quarter of the lake’s volume.” – BBC News

Nineteen years after, Pinatubo has become a popular destination in the Philippines, offering thrilling hikes and breathtaking views of its crater lake. One of the obvious benefits of this recent resurgence of interest is that it has become a new source of livelihood for the local community. But what has been less obvious is the fact that something so beautiful resulted from something so tragic.

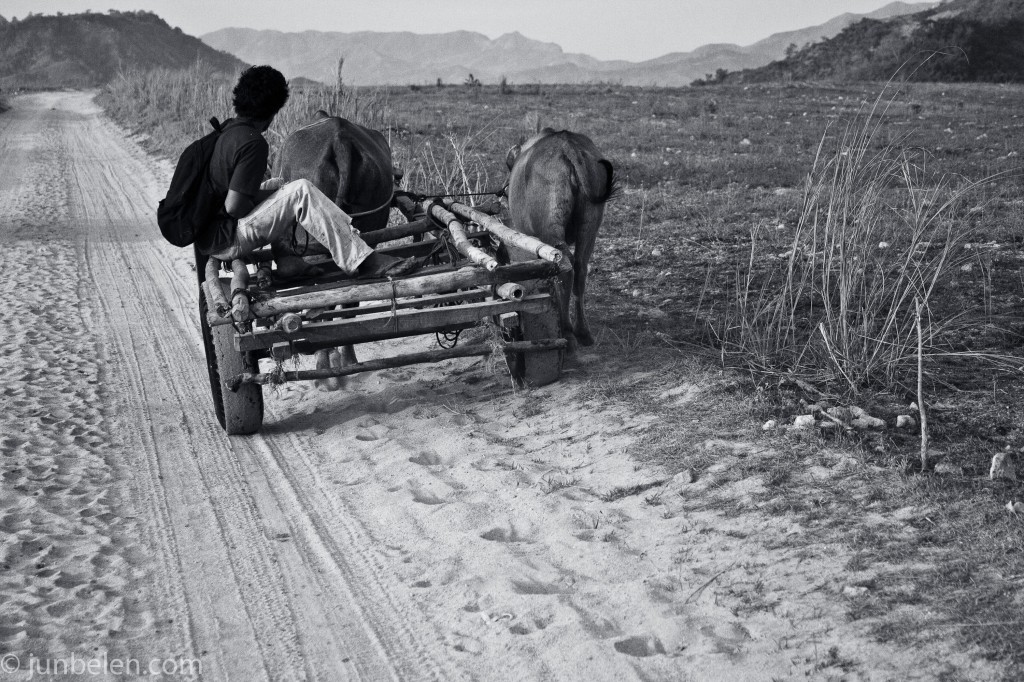

To get to the crater lake, we boarded an old, beaten-up 4×4 jeep and drove across Crow Valley. To describe the terrain as moon-like is an understatement. Aside from an herd of emaciated cattle and parched vegetation, sparse at times, Crow Valley is practically desolate. It was daybreak and so the soft morning light beautifully illuminated the dusty and rocky terrain and the steep and jagged cliffs. We shared the road with some locals — some on foot and some on carabaos — on their way to work.

As we got closer to the crater lake, we passed by a small community of Aetas. A small group of men, women and their children intently stared at us as we drove past their thatched-roof houses. It was quite emotional to see the children — scantily dressed and disheveled but with genuine smiles painted on their faces.

After a rough one-and-a-half-hour ride, we finally reached our destination. We were the first ones to park our jeep and take the 20-minute hike to the crater lake through a wooded forest. The hike was relatively easy. It was slightly uphill and we walked through rocky streams at times but more adventurous hikers can choose to take a longer, more challenging hike. It was already around 9 in the morning and the sun was already too hot. We were glad we took the shorter hike.

The view of Pinatubo’s crater lake was stunning. The rich turquoise water, mostly calm with fine ripples, surrounded by the volcano’s glorious crater walls was beautiful. Simply beautiful. We headed down to the beach and took a boat ride around the lake. Our guide pointed out west toward the notch in the crater rim that was cut to drain the lake almost a decade ago. The waters were calm and the breeze was refreshing. The only thing you can hear, aside from our chatter, was the sound of the wind gently blowing. It was incredible.

As much as we wanted to stay longer, we were ready to head back to Santa Juliana. It had been a long morning and our packed snacks of pan de sal sandwiches and pastillas de leche had almost run out. We were ready to enjoy the next part of the trip — lunch! Back at Pinatubo Spa Town, we feasted on pancit bihon (rice noodles), chop suey, adobong manok (chicken adobo), adobong kangkong (water spinach adobo), and endless bowls of steamed rice.

But we saved the best for last — sweet Zambales mangoes for dessert. Those sweet and buttery mangoes were the perfect sweet end to a perfect day.

For more Pinatubo photographs, follow this link to my photography portfolio.